This article was originally published by The Narwhal on September 24, 2021.

Plans to log old-growth forests in west-central Alberta, destroying habitat for some of Canada’s most threatened caribou herds, have sparked an outcry in the province.

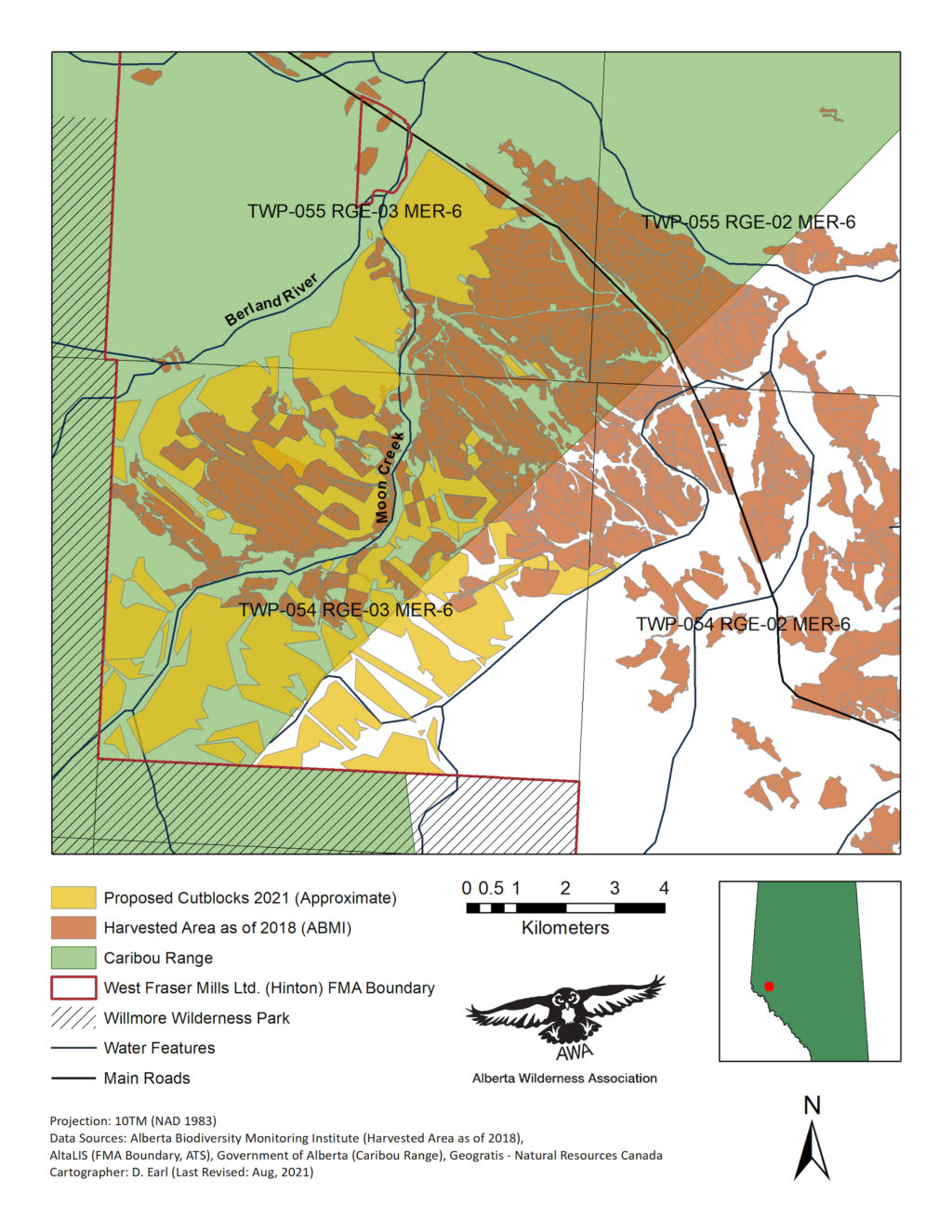

West Fraser Mills, a multinational wood products firm, intends to clear-cut 3,500 hectares of caribou habitat in the Berland area between Hinton and Grande Cache. The plan faces strong opposition from conservation groups such as the Alberta Wilderness Association, while the Mountain Métis Nation Association has said it will file an injunction to prevent the logging.

Many local residents are also opposed to logging and the Action for Berland Caribou Committee (ABC) has set up a blockade on a service road in an effort to prevent initial work. “The government must do their job and endorse sustainable logging in areas that don’t threaten endangered species,” the group said in a press release.

West Fraser did not respond to The Narwhal’s request for comment, but the company confirmed to other media that its logging plans follow the provincial government’s direction to operate in the Berland area until a local caribou recovery plan is completed in 2023.

Alberta’s Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry did not respond to questions about the logging proposal and caribou protection.

“It flies in the face of any common sense or reason,” Shane Ramstead, a local trapper and former conservation officer, told The Narwhal.

“You can’t say you’re going to do caribou protection and restoration of herds and habitats, and then go cut core habitat in the same ecosystem.”

Alberta government shoots and poisons wolves

Woodland caribou rely on old-growth forests. After forests are clear-cut, ungulates such as moose and deer move in to browse on new growth, attracting wolves and other predators that also prey on caribou.

The Central Mountain population of boreal woodland caribou — which includes the Little Smoky and A La Peche herds affected by the proposed logging — was designated as endangered by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada in 2014. A 2013 study found an approximate decline in the Alberta caribou population of 50 per cent every eight years.

“I think the Little Smoky in particular has been a poster child population for range disturbance,” Cole Burton, a conservation biologist at the University of British Columbia, said in an interview.

In 2005, the decline of caribou prompted the Alberta government to implement controversial predator control programs, such as shooting wolves from helicopters and poisoning them with strychnine. Alberta government figures show that between 2005 and 2017 the program killed 1,200 wolves and accidentally poisoned at least 250 other animals.

Although the measures were deemed necessary to protect caribou populations, industrial development in caribou habitat has continued. The amount of undisturbed habitat in the Little Smoky range dropped from five per cent in 2011 to one per cent in 2017 while only 12 per cent of the A La Peche herd’s winter range remains undisturbed — far below the 65 per cent undisturbed habitat minimum established by federal guidelines to give herds a 60 per cent chance of becoming self-sustaining.

The Alberta government recently proposed to build caribou maternity pens, an expensive approach used in B.C. with mixed results.

“Without the active wolf control that they’ve been doing for quite a few years now, we probably would be down to the last animals, or [the herds would] even [be] gone by now,” said Burton. “It’s really hanging on due to this heavy-handed approach.”

Ramstead pointed out predator control was not meant to be a long term solution.

“Shooting a wolf out of a helicopter is, they say, a drastic measure only for a short amount of time. But we’ve been doing it forever.”

Caribou versus Alberta resource extraction

The long-standing tension in Alberta between resource extraction and conservation efforts has increased in recent years, and the issue of caribou exemplifies the controversy.

After the federal government released a recovery strategy for boreal caribou in 2012, Alberta had five years to develop its own plan. Following inaction by successive provincial governments, the NDP government led by Rachel Notley initiated a planning process in 2017, only to put it on hold months later due to “socioeconomic” concerns.

Under the federal Species at Risk Act, Ottawa could have stepped in to enforce its own conservation measures. But the intervention was avoided through negotiations that culminated in 2020 with a joint agreement to restore woodland caribou populations in Alberta.

The provincial government also created sub-regional task forces to develop plans for protecting specific caribou populations, including in the Berland area. The task forces are expected to complete their work in 2023.

“It just seems wrong to do it without a range plan,” Darcy Handy, who has been trapping in the area for decades with Ramstead, said in an interview.

“It’s like they’re trying to sneak [the logging] in before the range plan is in place because they know if the feds don’t like the range plan, they’re going to come and monitor it themselves.”

In a press release announcing the blockade, the Action for Berland Caribou Committee noted the illogical practice of using predator control to protect caribou while simultaneously permitting the destruction of caribou habitat. “These programs have cost tens of millions of dollars, yet there have been no protected or deferred areas of habitat here, and the planned cutblocks are a direct contradiction to all of the money and efforts in place,” the release said.

A member of the group, who asked not be identified for fear of reprisals, said the blockade has been met with a positive reception, emphasizing that it’s strictly non-violent and seeks only to stop logging in caribou habitat.

They said the group has yet to hear from either West Fraser or the provincial government.

“We’re not anti-logging at all,” they said. “We realize that industry is a necessity. But this is the worst place to cut in Alberta.”

‘Gluttony and greed’

Burton said short-term actions intended to buy time for threatened caribou populations to recover — including predator control and penning — must dovetail with meaningful habitat protections.

“You can’t just have the wolf control without habitat protection, unless you’re planning on doing it forever in a hyper-managed situation,” he said.

But protecting habitat means keeping industry out, which is not something Alberta has traditionally found the political will to mandate. It’s a problem seen across Canada, where herds of caribou once numbering in the millions are now threatened or endangered.

“What we’ve struggled with is the transition,” Burton said. “If people in an area are dependent on extraction for jobs, we can’t just stop and leave those people out in the cold … We haven’t really envisioned ways to provide economic opportunities for people who are dependent on resource extraction that are compatible with protection for caribou habitat.”

Ramstead put it more bluntly.

“Of course it comes down to money,” he said. “Moratoriums on land means you don’t have oil and gas wells, you don’t have cutblocks …It’s all based on gluttony and greed.”

Ramstead and Handy said the West Fraser proposal has garnered consistent opposition from locals — in part, perhaps, because they are familiar with the government’s actions to date — even though many rely on resource extraction industries to earn a living. “It’s not defensible to these people. They know what’s been going on,” Ramstead said.

“It’s kind of baffling. [The provincial government] knows there’s going to be pushback and they’re going to have to answer questions. ‘Why would you do this without a range plan? Why would you do this without consulting the Métis Nation?’ I don’t understand much of what Jason Kenney is doing right now, frankly.”