The resilience of a wet meadow contrasted with a severely burned forest three years after the Cameron Peak Fire. Photo by Maya Daurio.

In the late summer of 2020, Colorado witnessed the largest wildfire in its history – the Cameron Peak Fire. This wildfire, which persisted for 112 days, burned over 208,000 acres of land while posing cascading consequences for people living in the Poudre Canyon community, including Maya and her family.

As a doctoral student in the Public Scholars Initiative at UBC, Maya Daurio received support from the Climate Emergency Fund (CEF) to expand research and community engagement efforts related to climate-enabled hazards. Using the fund, she is dedicated to fostering local community discussions around changes and impacts resulting from the wildfire.

As a doctoral student in the Public Scholars Initiative at UBC, Maya Daurio received support from the Climate Emergency Fund (CEF) to expand research and community engagement efforts related to climate-enabled hazards. Using the fund, she is dedicated to fostering local community discussions around changes and impacts resulting from the wildfire.

Words by Ruitong Zhao, Digital Content Creator, Sustainability Hub.

What sparked your interest in getting into this field of study?

It was a very personal experience. I was going to be studying issues around language and society in Nepal, and then suddenly my family’s historic home, which was in my family for about 130 years, was burned in the 2020 Cameron Peak Fire in Colorado.

Because the fire occurred during the pandemic, I was in Canada and I wasn’t able to travel, so the first time I visited was in the summer of 2021. And as it happened, while camping out on our land with my family, I also got to experience first-hand a flash flood in the creek that ran through my family’s land. This was a pivotal experience for me in deciding to turn my attention, in part for my own sensemaking, to how the Cameron Peak Fire and everything that the fire set in motion were impacting the community up here.

A flash flood on Sheep Creek in July 2021, the first summer after the wildfire. On this same day, two miles up the road, a debris flow on another tributary killed four people. Photo by Maya Daurio.

How is UBC's Climate Emergency Fund grant helping your research?

I'm so grateful for the funding because it allowed me to do at least three things of note.

To give you some context, this is a rural mountainous area – it's actually a canyon with a river that runs through it. Because of the geography of this landscape, there's inherently a lot of potential for hazards, and wildfire is a natural disturbance on the landscape. That kind of sets in motion a whole series of cascading hazards that accompany wildfire, and one of those is post-wildfire flooding that sometimes forms debris flows. So, I saw a need for facilitating discussion in the community around some of those hazards, and also around ways to potentially mitigate some of those hazards.

A representative from the Larimer Conservation District pointing out extensive fuel (tree) thinning to community members that helped reduce the severity of the Cameron Peak Fire in this area. Photo by Josh Roberts.

One of the things that I did was to organize a tour called the "Future of Forest Service Fuels Treatments." Fuels treatments, in this context, mostly mean either thinning trees, or putting prescribed fire on the landscape or a combination of both. The idea is that if you remove some of the fuel in the form of vegetation, it may help reduce the severity of wildfires.

The other important thing to know about the geography of this canyon is that 85% of the land is owned by the federal government, specifically the U.S. Forest Service, so the purpose of this tour was really twofold. One was to facilitate a greater understanding of what fuels treatments are, where they're occurring, and how previous fuels treatments interacted with The Cameron Peak Fire. The other was to facilitate relationship building between representatives from the federal agency and community members.

Participants of the "Post-Wildfire Flooding Tour" looking at log jams installed in a tributary to catch sediment and slow down water. Photo by Maya Daurio.

The other tour was a "Post-Wildfire Flooding Tour." We visited four different tributaries in the canyon, all of which have impacted both watershed quality, people's homes and land as well as forest service land. I worked with a fluvial geomorphologist (Colin Barry), who studies the distribution and change of streams and designed a lot of the flood mitigation infrastructure that’s been installed post-wildfire in this canyon.

We wanted to find out more about how different tributaries or streams have impacted land and people in the watershed, and also to talk about the different kinds of flood mitigation available and why some mitigation can work better in some areas versus others.

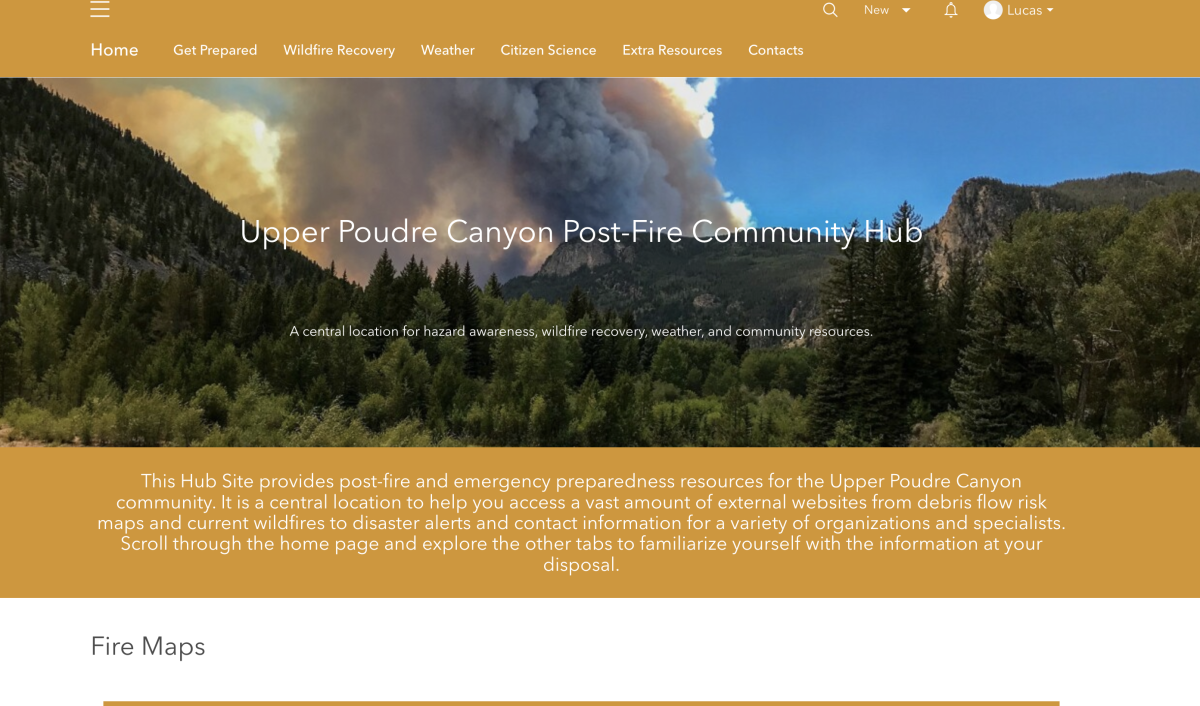

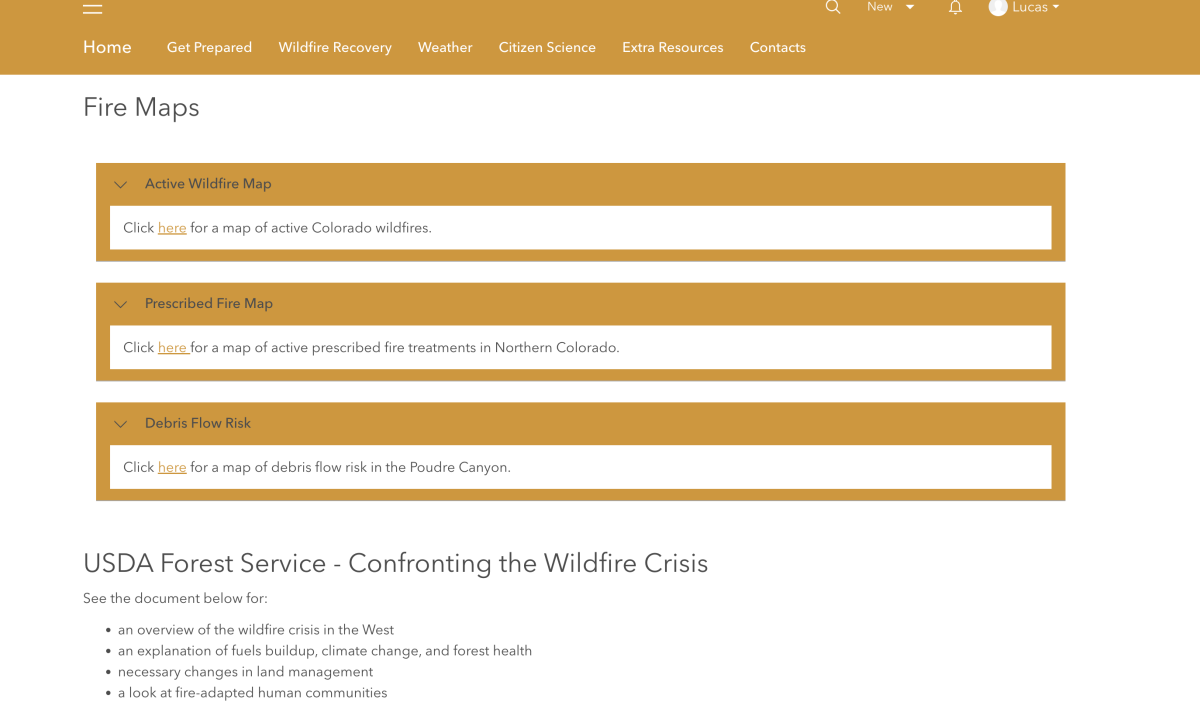

Third, I am working with the Geospatial Centroid at Colorado State University, which is the closest university to here. I'm working with a student intern named Lucas Roy to develop an ArcGIS Hub, which is essentially a website that has the capability to embed a lot of different kinds of interactive material in a way that’s easily digestible and visually appealing.

What do you hope to see as a result of creating the ArcGIS Hub website? How will it contribute to a more resilient future for the community?

Now we're three years out from the fire, and post-wildfire flooding impacts can last up to 10 years. They generally decrease in intensity each summer, but there's a real need for real-time information about rainfall, and there's a need for the ability to get information in a variety of ways.

After the wildfire, there was a lot of information out there, and it's quite difficult actually for any one person to make sense of all of the information. So, the purpose of creating the website is really to compile resources on behalf of the community – make sure people have access to resources and information that's useful for them in terms of this recovery period that we continue to be in.

I think that when you live through a disaster, that is, at the same time, also an ecological phenomenon. When a fire comes through a landscape like the way that the Cameron Peak Fire did, it really transforms the landscape, and there’s almost cognitive dissonance for people who have lived here their whole lives, or even for people who have known it for a shorter time.

Evidence of a debris flow, a mix of water and mud and rocks, on Little Beaver Creek, which was burned in the Cameron Peak Fire. Photo by Maya Daurio.

It's really important to understand both how wildfire and flooding can be a disaster for people, can have disastrous impacts on people's lives, and at the same time, that living through a disaster like this can also help us all better understand ecological processes and geomorphological processes on the landscape. It helps us understand the landscape as always undergoing change; it has the potential to help us all cope with uncertainty, to cope with maybe an even more uncertain future in the face of climate change.

Example of an older alluvial fan, a triangle-shaped area of deposition with gravel, sand, and smaller materials. It is created by flowing water fanning outward where steeper channels meet a flatter surface. Photo by Maya Daurio.

As a researcher who has been spending time in the field, how do you think your interactions with local residents contributed to the research?

One of the core methods of anthropology is participant observation, and this basically means that you participate in the daily lives of the people among whom you are conducting research.

The Stove Prairie Fire in March 2023, where Maya was working the line as a volunteer firefighter. Photo by Maya Daurio.

So, one way that I have done that is not only to live here, but I have also joined the local fire department (the Poudre Canyon Fire Protection District) as a volunteer, both as a way to contribute to the community and also as another way to engage in this method of participant observation, to better understand the role of emergency response in a rural, mountainous relatively remote area.

I have conducted a lot of recorded interviews with residents who live up here about their lived experiences and perspectives. I also have been interviewing scientists and researchers who are studying the impacts of this wildfire to understand how they’re thinking about it and making sense of it. I have accompanied a lot of scientists and researchers into the field, which has been a really wonderful way to better understand their work.

Can you speak to the goal of the ArcGIS Hub project aligning with your role as a researcher deeply connected to the local community?

I wear a number of hats here: I'm a researcher, I'm a volunteer firefighter, and I'm also a multigenerational resident of this community in many ways with a long family history. So, all of those things influence my perspective and also the way that I have sort of carved out a path for myself in relation to my research.

There's a real privilege in being a researcher, because you have access to potentially such a wide variety of people, or at least I do in my particular research project. It’s really important to me to be able to mobilize my unique position as a researcher in this community, my position of privilege, but also my position of access as a way to share those resources, to facilitate access for the community.

The fieldwork crew from the U.S. Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station based out of Fort Collins, Colorado, accompanied by Maya, on their way to perform a longitudinal survey focusing on biogeochemical hotspots in a post-fire watershed. Photo by Maya Daurio.